Posted on 29 August 2018.

By Donald H. Harrison

Donald H. Harrison

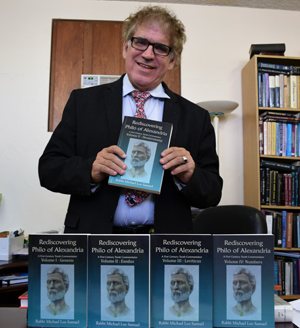

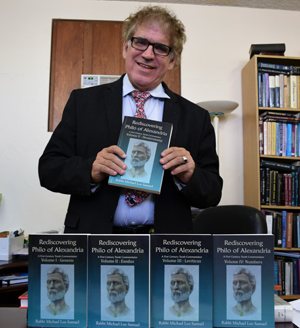

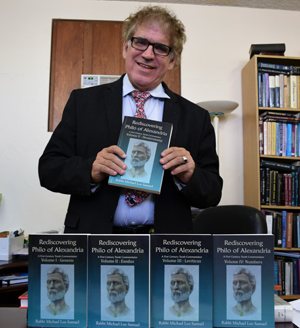

Rabbi Michael Leo Samuel and his 5-volume set on Philo’s Torah commentaries

CHULA VISTA, California – The 1stCentury Jewish philosopher and religious scholar, Philo, was very familiar with the Torah, commenting here and there on different portions of the Five Books of Moses in writings that were spread over approximately 40 publications in the native Greek language that he spoke in his home of Alexandria, Egypt.

Growing up in a Reform Jewish home, Michael Leo Samuel had been a fan of Philo’s since his early teenage years. His passion for reading Jewish texts eventually led to Samuel being ordained through the Lubavitcher (Chabad) movement, and then going on to serve as a Hebrew school teacher and a pulpit rabbi in Modern Orthodox and Conservative congregations. Recently, Samuel, who serves today as spiritual leader of Conservative Temple Beth Shalom in Chula Vista, has completed publication of a five-volume work, Rediscovering Philo of Alexandria, in which he pulls together Philo’s thoughts about Jewish scripture from Philo’s many writings and puts them into sequential order, thus creating for the first time Philo’s comprehensive commentary on the Torah. The books are available via Amazon.

To undertake this project, Samuel, who speaks Hebrew also taught himself Greek so he could read Philo in the original. He also drew upon the thoughts of some of Judaism’s later, and perhaps better known, commentators like Rashi, Maimonides, Nachmanides, and Ibn Ezra to illustrate how Philo’s commentaries in some cases presaged the thoughts of these great commentators and in other instances contradicted them.

Rediscovering Philo of Alexandria relates in order Philo’s commentaries on Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy.

In a wide-ranging interview, Samuel, who contributes occasional columns to San Diego Jewish World, discussed his books and the philosopher who inspired it. He also is accepting invitations to discuss the book at synagogue, chavurah, and club gatherings.

He said that while living in First Century C.E. Alexandria, Philo faced two conflicting forces during his life. On the positive side, Alexandria was a cosmopolitan port city which treasured learning, as was exemplified by its world-famous library. On the other hand, many native Egyptians harbored anti-Semitic attitudes, making life in Alexandria a wary experience for Jews. “One of the great pogroms in Alexandria that took place in the year 30 or so, resulted in the death of 50,000 people,” Samuel commented. “It was the first modern pogrom of late antiquity. Philo gives eye witness to how Jews were not even allowed to bury the dead, and the Roman prefect in Alexandria, Flaccus, was always trying to curry favor with the local anti-Semitic population.”

Nevertheless, Philo manage to enjoy some of what life had to offer. “One of the things that I like about Philo was that he was an Alexandrian Jew, much like today we are American Jews,” said Samuel. “He would attend the gymnasium, watch wrestling matches. He would attend Olympic-style games. He would go to horse races, and he had an interest in sports and would often draw some profound spiritual analogies about Jewish spirituality from sporting events that took place in his time.”

As a commentator, Philo was willing to opine on issues that continue to be controversial to the present day. Abortion, homosexuality, and how Jews should treat other religions were among the subjects to which Philo gave deep thought. Living in the pre-rabbinic era of Judaism, his commentaries often were in sharp contrast to those of later Jewish scholars, according to Samuel.

Whereas many later commentators took every word of the Torah literally, Philo was one of the first Jewish scholars to suggest that it must instead be understood as an allegory from which lessons may be learned, even if every word is not true. In Philo’s view, according to Samuel, the Torah was given to the Jewish people at a time when they were not far removed from slavery. Intellectually, they were like children, unable to understand complex rationales. So, in the Torah, God warns the Jews of adverse consequences if they don’t follow His law, much like a parent warning a child, “Eat your dinner, or there will be no dessert.”

Philo differed with more recent commentators over the passage in Leviticus which describes as an “abomination” or an “abhorrence” the situation of a male lying with another male as with a woman. Samuel said, “Philo explains that this is a statement that deals primarily with pedophilia and he gives many examples from Greek society how boys were often paraded around like women, under the tutelage of an older male adult. He said this was what the Torah forbids; the reason that he said this was forbidden was a man has to be manly; to make a man womanly is degrading …. That approach might not fly in modern times, but his concern about the exploitation about children is definitely an important issue to bring up.”

Most rabbinical commentators in later periods did not address the problem of pedophilia at all, according to Samuel. What little discussion there was seemed to wink at the problem, Samuel said. “The rabbis (of the Talmud) did not have a concept of pedophilia, one of the shocking aspects of Talmudic history that frankly is very embarrassing,” he added. “Philo stands head and shoulders above.”

On the issue of abortion, Philo definitely would have been on the “pro-life” side of the debate, rather than the “pro-choice” side, said Samuel.

“Philo had tremendous respect for prenatal life,” Samuel said. “He considered abortion to be immoral. It is not clear whether he believed that life began at conception, but certainly in the last trimester of a fetus’s life, he said that the fetus is like a statue that has been prepared—only needs to be uncovered and exposed to the world. Beautiful analogy.”

In contrast, others in the ancient world seemingly were unconcerned with the unborn babies. “If a woman was accused of adultery, she would drink this potion that came from the earth of the sanctuary—and if she was guilty her stomach would explode,” Samuel said. “So, if she were pregnant with another man’s child, she would die and the child would also. That’s implied in Scripture,” Samuel said.

In some early rabbinic writings, he added, “If a woman is a murderess and is about to be condemned for that murder, but she is pregnant, the rabbis say you take a club and you smash her stomach even to the time till she is almost ready to deliver, to kill the baby. Because the mother is so unhappy that the child is going to grow up without a parent; better for the child to die than to endorse such a sadness. Rabbinic thinking! If those rabbis had been familiar with Philo’s argument, he had turned that argument on its head. He said, just as you are not allowed to slaughter a calf and its mother on the same day, this applies to animals, how much more so to human beings. So, if you have a case where a woman is condemned, and she is about to give birth, you do not execute her with the child – that would be an act of murder. That would be treating a human with less dignity than an animal with its young. Therefore, you have to wait for the mother to give birth, nurse the child, and a later time execute the mother.”

Samuel added, “These discussions were really theoretical, the reason being that Rome did not allow Jews to practice the death penalty.”

Respect for all religions was a hallmark of Philo’s thinking, Samuel said. “One of the laws in the Torah is that we are not allowed to curse God – and Philo understood this to mean not only are you not allowed to curse God; you are not allowed to curse the gods of other peoples. Now when I was a yeshiva student many years ago, I remember how many of my friends in the Lubavitcher community would walk by a church and they would always spit on the sidewalk. In fact, they spit whenever they mentioned idols in the Aleinu prayer, and even from the most Orthodox perspective that is considered a risqué and halachically scandalous behavior. You don’t spit in a synagogue; it is considered inappropriate.”

Samuel’s first book was an outgrowth of his doctoral thesis at the San Francisco Theological Seminary. The Lord is My Shepherd: The Theology of a Caring God was followed by five other books on diverse topics, and then this five-book series. A workaholic, Samuel said he never lets a day go by without writing at least three pages and sometimes, if the juices are flowing, he might write 20. He said that he has as many as 50 books in various stages of completion, with some of them likely to be published later this year or early in 2019.

Rabbi Israel Drazin, one of the most prolific writers on biblical topics with books to his credit about the Prophet Samuel, King David, King Solomon, Jonah, Amos, The Aramaic translation of the Bible known as the Targum Onkelos, and various other commentaries, has reviewed Rabbi Samuel’s work on Amazon, giving it a five-star rating. “Until recently, it was Harry Wolfson’s 1962-1968 two-volume work Philo: Foundations of Religious Philosophy in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam that was considered the authoritative book on Philo of Alexandria, Egypt (ca. 20 BCE to about 50 CE),” Drazin wrote. “Today, because of the wealth of scholarly material contained in his five volumes and their presentation in a very readable manner, Rabbi Michael Leo Samuel’s books can now be considered the authoritative work on the great Greek Jewish philosopher.”

*

Harrison is editor of San Diego Jewish World. He may be contacted via donald.harrison@sdjewishworld.com