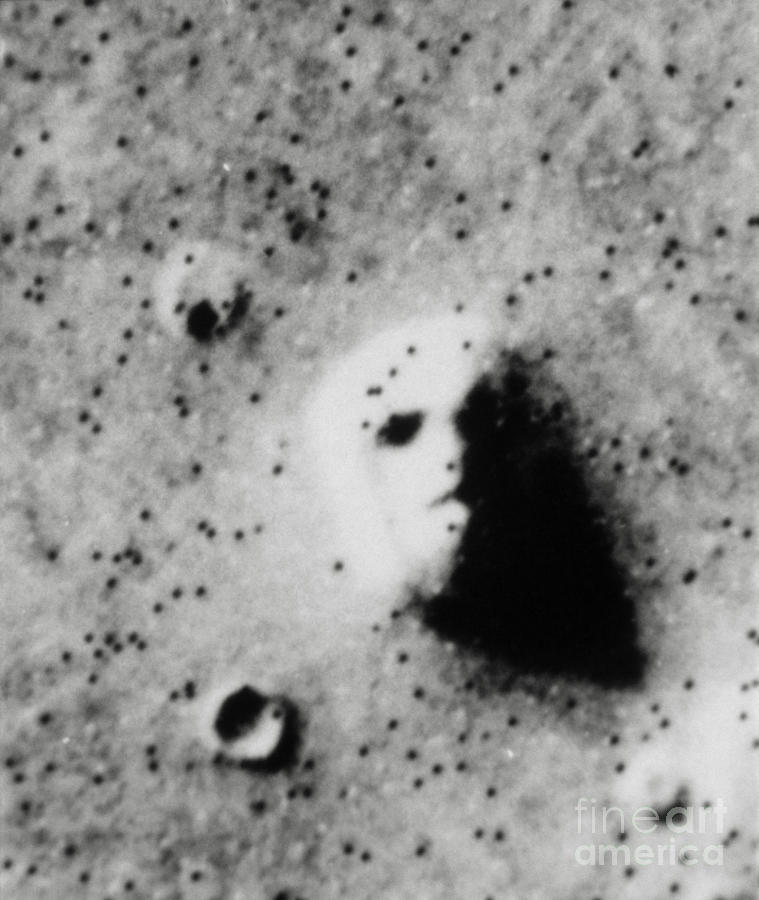

Bear Face on Mars?

Does Nature have a sense of humor?

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter snapped a view of Mars that will likely trigger your pareidolia instincts. Pareidolia is the human tendency to see familiar objects in random shapes. In this case, you’re totally looking at a bear. The Observatory at the University of Arizona took this picture, just the other day.

The “face,” captured by MRO in December, is bigger than your average bear. A version of the image with a scale shows it stretches roughly 2,000 meters (6,560 feet) across.

Anthropologists, psychologists, and theologians refer to this as ” pareidolia” Defined: Pareidolia the perception of apparently significant patterns or recognizable images, especially faces, in random or accidental arrangements of shapes and lines. Some people see Jesus’s face smiling at them from the sky, others might see Mohammed or Buddha. Seeing the famous man in the moon or the canals on Mars are classic examples from astronomy. The ability to experience pareidolia is more developed in some people and less in others.

For a sweeping critique of how anthropomorphism affected science and philosophy from ancient to modern times, the anthropologist Stewart Elliot Guthrie’s book, Faces in the Clouds stands out as an exceptional work. He theorizes that anthropomorphisms represent a perceptual strategy of how humanity perceives itself in an uncertain world. If, for instance, we see a dark shape in the forest, it is better to assume it is a bear and not a boulder. Guthrie’s innovative idea is patterned after the famous wager of Pascal.[1] If what we are observing truly resembles human behavior, then our use of anthropomorphic language is correct. If we are wrong, what did we lose by employing anthropomorphism? In a world where scientific analysis fails or is severely limited, human beings consciously and unconsciously gravitate toward imagining the universe in the likeness of themselves.

Historically, several cultures worldwide developed myths regarding the mysterious “man on the moon” images before the space probe was launched. On July 25, 1976, the Viking 1 probe took some unusual photographs of the Cydonian region of Mars, which presented land formations resembling human faces, and hence came to be known as the “Face of Mars.” Scientists soon dismissed this interpretation and said that the image was a “trick of light and shadow.” The human mind always projects images of its own likeness unto the universe. For Guthrie, the same principle applies no less concerning religion. For him, religion is the embodiment of anthropomorphism.

Guthrie makes a thought-provoking point. Whenever people try to explain abstract processes they do not understand, the tendency is to use metaphorical language, for it helps people connect with subtle and not easily defined ideas. [2] According to Guthrie, the various branches of science, cognitive sciences, ancient and modern philosophy, and the literary and visual arts abound with anthropomorphism, even though secular scientists and philosophers often criticize it.

Guthrie’s observation is on target. Human speech uses the metaphor for even inanimate objects or when describing a force of nature as if it the object or effect being described possesses human-like qualities or actions. Thus, we metaphorically speak of a storm as “vicious” or “threatening,” or “the wind howls throughout the night.” Even in scientific terms, physicians and biologists frequently refer to white blood cells as “fighting off” and “invading” microorganisms, or the “selfish gene,” or “the blind watchmaker” (to borrow a phrase from Richard Dawkins’s popular book). Analogical language is vital for understanding the religious expression and is no less essential for discerning scientific truths about reality.

Scientists illustrate the most abstract mathematical truths through the medium of analogies. Models of science contribute to a more in-depth knowledge of already existing theories. Verbal representations provide a mental picture of an obtuse concept that facilitates a quicker and clearer understanding that is superior to the presentation of mere abstract equations. For example, it is impossible to explain the nature of time when describing the nature of time; the scientist and poet alike illustrate time through metaphor. Thus, we speak of time as “flowing like a river” or as “an arrow shooting toward infinity.”

When speaking about non-spatial reality or scientific abstractions such as Quantum physics, the scientist must utilize metaphor to convey the idea that he or she wishes to express. Linguists have long recognized that it is virtually impossible to talk about time without the use of metaphor. Without metaphor, the human mind would have an extraordinarily difficult time conceptualizing abstract images that are too difficult to describe in literal terms. More importantly, metaphoric language reveals underlying conceptual mappings and psychological structure of how ordinary people imagine knowledge’s ambiguous, abstract domains through their embodied experiences of the world. Myrmecologists study the lives of ants and use anthropomorphism in naming ants as queen, worker, soldier, parasite, and slave. They define ant communities in terms of classes and castes, thus making ant behavior seem incredibly human.

Ancient poets and storytellers of the Bible recognized a similar truth when attempting to describe the greatest abstraction the human mind has ever entertained—God. Thus, both Jewish and Christian theological traditions stress that the role of metaphor is not purely a decorative embellishment of human language but is an essential method by which people conceptualize the world around them and their own activities. When studying the metaphors of a classical work such as the Bible, grasping the spirit of the text requires that one approach the book and its unique metaphors in a culturally sensitive, ethical, and heart-centered way. Metaphor plays a significant role in developing our social, cultural, theological, and psychological reality. Perhaps more decisively, metaphor can reshape the imagination and the thought process. It allows us, the readers, to transcend the realm of the ordinary.

Therefore, uses of metaphorical and anthropomorphic language are not concessions to the popular imagination, as some philosophers might have us believe. Nor are they deployed purely for their psychological impact upon the reader or listening audience. The prophetic imagination never uses the noetic language of logic or prose, but instead employs the rhetoric of poetry and hyperbole. We could even say that prophetic speech would be very ineffective without it. Sensuous and symbolic, prophecy always appeals to the receiver’s imagination[3] and life experiences.[4] The prophet’s oratory skills gripped his listeners’ attention. When God’s Word inspired him, he felt instantly energized with a heightened awareness and ability to articulate dramatic speech. The Protestant theologian Walter Brueggemann adds an insight about the relationship between prophecy and poetry that dovetails with Saadia’s earlier remarks:

By prose, I refer to a world that is organized in settled formulae so that even pastoral prayers and love letters sound like memos. By poetry, I do not mean rhyme, rhythm, or meter, but language that moves like Bob Gibson’s fastball that jumps at the right moment; that breaks old worlds with surprise, abrasion, and pace.[5]

Sometimes, the prophet’s personal life becomes the very image and the metaphor of God’s message to the people. For example, God commanded the prophet Hosea to marry a whore (Hosea 1:2-9). Similarly, the story of Jonah illustrates how the life of a stubborn prophet reflects the persistent nature of the people he represents. The Book of Jonah is replete with imagery and metaphors depicting the paradoxical nature of God’s own “stubborn” love and forgiveness. In a pedagogical sense, the prophet became a living embodiment of God’s Word, passionately revealing God’s “human-like” personality and character to the world.

The early Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico (1668-1744) believed metaphors and allegories were not merely calculated forms of language or a product of human convention. The metaphor was first a product of the mind—and not language. Metaphor allows people to make associations that create cognition. Vico was one of the first pre-modern thinkers to speak about a poetic logic that creates perceptual models that make even inanimate things come alive. A metaphor is “fable-making,” he said, viewing each metaphor as a fable (or analogy) in brief.

Concerning metaphor, in particular, Vico also thought that metaphor can animate nature, “giving sense and passion to insensate things… that in all languages, the greater part of the expressions relating to inanimate things are formed by metaphor from the human body and its parts and from human senses and passions.” Thus, in metaphor and imagery, we coexist with the world surrounding us, which we view as a soulful extension of ourselves. The use of metaphor makes it possible for us to cultivate and expand the power of the human imagination that is essential for spiritual life.

The German philosopher Martin Heidegger (whose Nazi past we shall overlook for the present) made brilliant observations about human language’s nature and its relationship to metaphor and poetry.

It is language that tells us about the nature of a thing, provided that we respect language’s own nature. In the meantime, to be sure, there rages round the earth an unbridled yet clever talking, writing, and broadcasting of spoken words. Man acts as though he were the shaper and master of language, while in fact language remains the master of man. Perhaps it is before all else man subverts this relation of dominance that drives his nature into alienation. That we retain a concern for care in speaking is all to the good, but it is of no help to us as long as a language still serves us even then only as a means of expression. Among all the appeals that we human beings, on our part, can help to be voiced, language is the highest and everywhere the first.[6] (Emphasis added.)

The poet perceives reality very differently from the thinker. The rationalist may be an excellent wordsmith and be capable of expressing a clear and lucid thought. However, the poet is governed by a different principle; his heart speaks volumes that can be scarcely expressed by words alone. Yet, when we read the poet’s words, the poet affects us far differently than

[1] According to Pascal, “If God exists, the religious believer can look forward to ‘an infinity of happy life’; if there is no God, then nothing has been sacrificed by becoming a believer (“What have you got to lose?” asks Pascal). In simple terms, Pascal stressed that it is better to live a life of faith that gives ultimate meaning than to choose living a life that has no ultimate meaning.

[2] Stuart Elliot Guthrie, Faces in the Clouds—A New Theory of Religion (New York: Oxford University Press; Oxford, 1993), ch. 6.

[3] Even Maimonides admits the process of revelation always contains anthropomorphic imagery, without which God’s message to the prophet could never be known (Maimonides, MT Hilkhot Yesodei HaTorah 1:9).

[4] An interesting parallel may also be drawn from Hinduism. Lord Krishna said in the Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 12, Verse 5, that it is much more difficult to focus on God as the unmanifested than God with form, i.e., using anthropomorphic icons (murtis), due to human beings’ need to perceive via the senses.

[5] Walter Brueggemann, Finally Comes the Poet (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1989), 3.

[6] Martin Heidegger and Albert Hofstadter (trans.), Poetry, Language, Thought (New York: Harper and Row Perennial Classics, 1971, rep. 2001), 144.